by Susan Couso

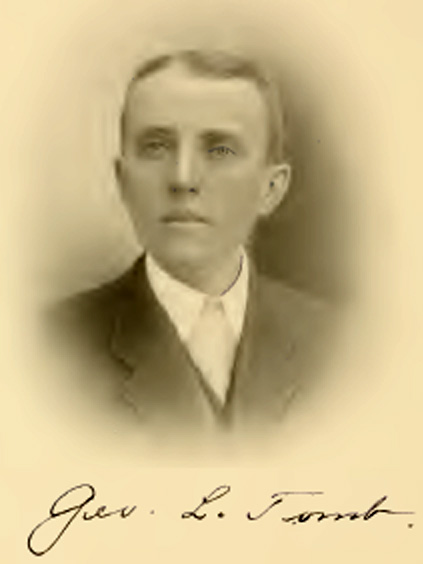

Nurture vs. nature has long been a topic of debate, but no one will ever know what makes some people do the things that they do. Take George Lincoln Tomb.

George was born in Newburgh, New York in 1868, but things did not go well. Soon after his birth, his mother, Harriet O’Dell Tomb died, leaving little George in the sole care of his father, Charles. Charles was a saddle, harness, and trunk maker, and had little skill or time for a newborn.

So, little George was sent away to New York City and put into the care of his aunt, Jane O’Dell Smiley. By 1880, his father had remarried, and 7-year-old George was returned and put under the guidance of his new stepmother, Geraldine.

George had attended public school while in New York with his aunt, and when he returned to his father, his education continued. But when George was seventeen years old, his father died, and his world changed again.

His inheritance included his father’s gold watch, some personal belongings, and a small amount of money, with his stepmother getting the majority of the estate. George then returned to New York City and secured a position as a clerk.

In 1889, George decided to try his luck ‘out west’ and traveled to San Francisco. He easily found work as a clerk, but for some unknown reason, George then decided to travel to Susanville in 1890. He was first employed as a clerk for the Odette lumber mill, but by 1898 he decided to run for the position of Lassen County Clerk.

Tomb successfully mastered the election and was sworn in on January 1, 1899. In 1902, he was again elected, and his second term was to last until 1907.

George was a respected member of the community. He was well-liked and trusted. In the late 1890’s he was chosen as a delegate to the state Republican Convention. By 1904, he was the general manager of the Beckwith & Greenville Stage Line. In 1905, he purchased Alonzo Philbrook’s furniture and undertaking business on the corner of Main and Gay Streets and was secured as one of Susanville’s leading businessmen.

In 1897, he had married Maud Long in Susanville. About 1900, they had a baby son who died, but Maud and George went on to have two little girls, Nadene and Gladys. By 1903, the girls had made their family complete, and everything seemed pretty darn perfect. But George had a ‘problem’.

Unknown to most of the small town, George liked to drink and to gamble, and these things do not usually mix to the advantage of the imbiber. He often traveled to Reno and beyond, ostensibly on business. But the lure of the gambling halls was just too much for Tomb. He struggled to overcome the urge, but, instead, became embroiled in debt.

Just past the ‘turn’ of the 20th century, Lassen County citizens voted to build a new high school, and George Tomb helped with the project. Who better than the County Clerk? No one seemed to understand the depth of George’s problems.

The new heating plant for the high school cost a lot of money, and George, who was in charge of this money, had an excellent idea. He could take the money as a ‘grubstake’ and go to the gambling halls of Reno and turn it into enough profit to cover all of his debts, and then return the money to the school fund. But that did not work.

As was the usual, George lost it all. He was frantic, and he was in trouble. When news of his indebtedness and the loss of the heating plant money reached authorities, the County Recorder issued a warrant for the return of the money from the high school account. Things were deteriorating quickly.

George was credited with being one of Lassen County’s best elected officials, and he was praised for his work. He had numerous friends in the area who themselves had taken leading roles in the community.

A group of these friends got together and contributed money to cover George’s debt. They paid between $100 and $1,000 each, and allowed George’s money mishandling to be kept quiet.

The friendship that these men showed was, of course, appreciated, but that did not settle the matter. George was still hopelessly in debt. His business and home were in jeopardy, and his accounts were all overdrawn. So, by the first of September 1906, George decided to leave town, abandoning his county position, his business, and his family.

His departure strained his relationship with his friends, who feared the loss of their hard-earned money, and startled his wife, Maud, who had no idea of the seriousness of the situation.

As George passed through Standish, he sent a note home to Maud, telling her that he would not ever return. Maud was left with an enormous debt, no job and two small daughters to care for. The local populace had tremendous sympathy for her predicament.

Now, the word was out, and the community spent a great deal of time assessing the situation. All of Tomb’s property was attached, in an effort to allow creditors to recall some of their money, but it was expected to be a total loss for most of them, and those that could recover something could only expect about 4 cents on the dollar.

The County Board of Supervisors planned to meet to appoint a new County Clerk. But on Monday evening, September 3rd, George returned and continued in his elected position as County Clerk. He took great effort to defend his actions in all of the newspapers, and set about trying to repair his image. He claimed that, as all businessmen, he owed money, but all accounts would be paid ‘in full’.

By November, George L. Tomb was in bankruptcy court. He had creditors in Sacramento, San Francisco, Reno, Stockton, Tonopah, Oakland, and “numerous other places.” His total indebtedness was listed as $25,548. That’s roughly $830,000 in our current economy.

In 1907, the voters declined to reelect Tomb, and replaced him with George E. Bassett.

George L. Tomb had a new job all lined up in Tehama County where he worked as a bookkeeper for the Los Molinas Land Company. He sold his remaining assets in Lassen County, and moved his small family to the valley. Unfortunately, old habits returned, and within just a few months, Maud took her daughters and left George behind.

1908 was a busy year for Tomb. On July 20, 1908 he was admitted, by examination, to practice law in the State of California Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, third district court, California , and he listed his residence as ‘Susanville’ and his occupation as ‘attorney’.

On October 30, 1908, he was appointed Postmaster of Los Molinos, Tehama County, and in the City Directory for Sacramento, he was listed as a clerk who rented a room at 1016 ½ ‘J’ Street. Clearly, Tomb was trying everything that he could to ‘make a go’ of his situation.

After Maud left, he continued working in Tehama County, but ran into some trouble when he was accused of discrepancies in the books. Some defended him, saying that the money was not missing.

But on March 15th, 1909, George L. Tomb disappeared. He had complained of a toothache and said that he was going to Chico, and then he vanished.

A short time after his disappearance, Maude received a note from him, along with her watch. He was thought to have visited friends in Sacramento, and newspapers circulated a notice there that Tomb was missing. But to no avail.

In January of 1912, Maud received a divorce from George. The grounds for the divorce were ‘desertion’.

In January of 1914, the Bank of Tehama County sued Tomb. Officials could never serve the summons, and George Lincoln Tomb was never seen or heard from again.

If you are a fan of our weekly history stories you should join the Lassen County Historical Society! It’s a fun way to be a part of our county’s rich history. When you sign up, you’ll receive regular Historical Society newsletters with interesting stories and information. Membership is open to anyone with an interest in area history.

Through your membership you help preserve local history. You can download a membership application by clicking here.