by Susan Couso

Honey Lake City was a beautiful place. The city was expertly planned and laid out to accommodate the future growth of the area. It boasted churches, theaters, a university and an opera house.

It even had electric cars, which traversed the broad avenues and boulevards. Tall trees and lush foliage, fed by the abundant water from Lake Greeno, kept the entire area beautiful.

The surrounding countryside was covered with abundant agricultural endeavors, and the populace was well supplied by the many commercial opportunities in the city.

But it never happened. It was all the chimerical adventure of a small group of men, who had hoped to make a new metropolis, and a fortune. And it was dashed by poor planning, mismanagement, and good old Mother Nature.

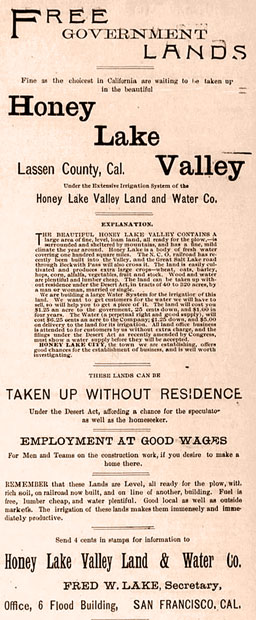

In June of 1891, the Honey Lake Land and Water Company was incorporated in San Francisco. The main organizers and planners consisted of: Jerome B. Cox, president, Frank M. Shideler, vice-president, Fred W. Lake, secretary and treasurer, and L. H. Taylor, engineer, and chief in charge of construction.

As soon as the papers were filed, a prospectus was presented to the public, laying out the costs and income potential of the project. These men may have begun this adventure with hopes and dreams and good intentions, but soon, by using small prevarications and outright lies, prompted many hard-working men to invest their time and money in a scheme which was sure to fail.

The plan was to build a dam, just south of Honey Lake, and contain the waters of Long Valley Creek in a huge lake. It was to be named Lake Greeno, in honor of a local pioneer and rancher, George Greeno.

The dam was to be 96 feet tall and 500 feet wide at the base. The top of the dam was to be 950 feet wide. This created a total reservoir capacity of 10,733,700,000 gallons. The water was to be carried across Long Valley Creek via a 1,000’ long flume, which fed into the distribution canals.

There were to be 24 miles of larger canals, 28 miles of secondary canals, and 57 miles of distribution ditches. This water was to turn the arid area into an agricultural mecca.

The basis for this scheme was the Desert Land act of 1891, which encouraged people to ‘prove up’ on desert lands and make them fruitful. The Honey Lake Valley Land and Water Company would simply help by planning and providing the water.

The Honey Lake Land and Water Co. offered to sell the land for $7.50 per acre. The purchasers would pay $1.50 per acre when they made the deal, with $.25 going to the government, and $1.25 going to the promoters.

When the water was delivered to their land, they would pay an additional $5.00 to the promoters and the final $1.00 would be paid to the Land Office in Susanville within four years. The promoters would handle the paperwork for the new Lassen County citizens.

Purchasers were also ‘allowed’ to buy water rights for an additional $5.00 per acre, with yearly fees for water delivery set at $.25 per acre for the first year and ascending to $1.00 per acre for year three and beyond.

The best part of the entire promotion for many was the offer to purchase this land and water by working. The men could pay $5.00 down to enter into a working contract where they would be paid at the rate of $60 per month. Fifteen dollars per month was deducted for ‘room and board’, and $40 was credited on payment for water. Men who brought their own teams of work horses were paid extra.

So, the deal was set. It was reported that over 1,000 lots were sold, and construction was ‘fast and furious’. Men came from all over and many brought their families, their teams of horses, and everything they possessed. Their dreams of ownership and prosperity propelled their arduous, difficult, dusty work.

The small cabins provided by the company were made of rough unpainted lumber and constructed hastily. Families crowded into some of them, and some were shared by single men. They all had berths fastened to the walls where the higher bunks were reached by climbing a small ladder and then through a hole to reach the bed. It was rough at best. Some of the hopefuls chose to camp in tents, looking out on their land.

It soon became apparent that the prospectus presented by the company was not plausible. The costs far exceeded any predictions, and the Honey Lake Land and Water Company was near bankruptcy. Workers were not being paid, but they clung to their hopes. Mostly, they had no money to leave, and their only chance was to continue working.

Workers began to complain about the provisions provided at the store. They had a $15 per month allowance for food, but often there was little available. Basic staples were missing and things like meat, sugar and coffee were unavailable.

By the fall of 1892, work was progressing, but many onlookers were beginning to worry. Rain was coming, and the dam was not ready to hold any quantity of water. Some questioned the preparations and studies done by engineer Taylor. He was the chief of the entire project, and yet, he seemed to take minimal care in his work.

The rains began. Although warned by local residents, who had seen the power of Long Valley Creek in its fury, the promoters held confidence in their engineer. But in November, the powerful, uncontrollable creek won. The surging water tore through the unfinished dam and destroyed the many months of work.

The company, in an effort to save their money, came up with a new plan. They determined that they needed an additional $150,000 to finish the work, and then sent out notices that the land purchasers needed to pay more. Most, if not all, of the men who had been working for their land, had not been paid. Many had learned that, after paying the initial costs to the company, their land claims had not been registered. Now, they were in a position where they had no wages, no land, and nowhere to go.

The Honey Lake Valley Land Company notified the land purchasers that now water rights would cost $10 instead of $5, hoping that those duped by the company would, for some unknown reason, come to their rescue. The purchasers realized that if they did not pay, their land would be as dry as the surrounding desert, and their hopes of a verdant farmland were gone. It was, quite simply, ‘blackmail’.

There was no future in Honey Lake City. The company had placed white stakes in the desert to mark the streets and avenues, along with; University Avenue, the opera house, and the First Episcopalian Church, among others. But nothing more. There were only white stakes.

The miles of canals lay in idea only, and Long Valley Creek went just where it wanted. It was a complete loss. But the biggest loss was to the people involved in the Honey Lake Valley Land and Water Company scheme.

As the project died, thousands of dollars of hard-earned money were gone. Families were left sitting in the desert with nowhere to go and no money to get there. It was feared that these people would starve if help did not come. And those that could, bitterly left Lassen County to begin again somewhere else, poorer but wiser.

Most of the blame fell of Taylor, whose perfunctory methods of engineering caused it all. The dream was gone, the work was over, there was no Lake Greeno, and there was no Honey Lake City.

If you are a fan of our weekly history stories you should join the Lassen County Historical Society! It’s a fun way to be a part of our county’s rich history. When you sign up, you’ll receive regular Historical Society newsletters with interesting stories and information. Membership is open to anyone with an interest in area history.

Through your membership you help preserve local history. You can download a membership application by clicking here.