by Susan Couso

Before 1912, Susanville had no real hospital. What was labeled as a hospital was mainly an ‘old folks home’ for those who had no one else to care for them and nowhere else to go. Doctors visited patients in their homes and even performed surgeries there, often operating on the kitchen table.

Then, Dr. Robert Garner and Dr. Edward Drucks decided to do something about it. They leased a home from Mrs. Susan Brashear for a county hospital, purchased medical equipment and supplies and hired a staff.

With a ‘real’ hospital available for the first time, Susanville was able to better care for many of its citizens.

The Utah Construction Company was awarded a contract to construct the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks through Susanville, in 1912. As the Utah Construction Company’s railroad workers came to the area to build the railway through town, they found it necessary to have medical facilities for their employees.

The company, head-quartered in San Francisco, charged their employees 75 cents per month for a hospital fee. The employees then got ‘free’ medical care. Utah Construction contracted with Dr. Garner and Dr. Drucks to provide the care in Susanville.

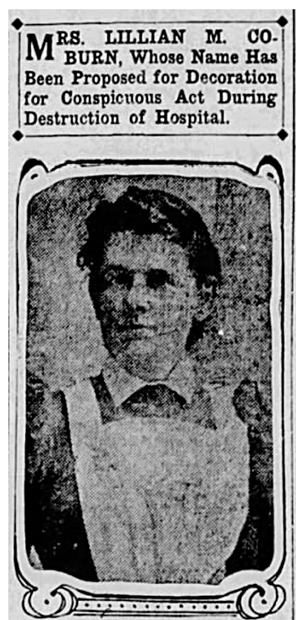

This was a ‘boon’ to the hospital, which hired new employees to accommodate the expected patients. One of these employees, Lillian Coburn was hired as the hospital Matron, a position which oversaw the nursing staff. Mrs. Coburn had previously been one of six nurses who worked for six weeks per year tending to pediatric patients in the ‘Little Jim Ward’ in San Francisco.

Lillian Coburn had immigrated to the U. S. from Scotland in 1875. The then Lillian McDonald was only five years old. In 1913, she was a 43-year-old widow with a 12-year-old son named Donald.

By September 1st, the railroad was completed to Susanville, and there was regular freight service, but Utah Construction still had about 1,000 men working to build the portion of the railroad between Susanville and Devil’s Corral.

Then, on September 7th, at 7 o’clock in the morning, disaster struck the hospital.

Sixty-two-year-old William D. Minckler was a patient in the hospital, suffering from severe rheumatism, and his 24-year-old son, William D. Minckler, Jr. was also a patient. The junior Minckler had been in a motorcycle accident and suffered a severe head injury with a concussion. The senior Minckler was chilled, and a coal oil heater had been set up in his room to warm the room for his bath.

Apparently, Senior Minckler was a bit confused, and unwittingly knocked over the heater, which exploded and started a fire in the room. The spilled fuel spread rapidly.

As the fire was discovered, the alarm was sounded. There were 17 patients, who were removed as quickly as possible. Lillian Coburn confronted the confused Senior Minckler and got him out of the room, telling him to go outside, but he just stood in the hall.

She then turned to the room next door, which was occupied by Junior Minckler. She tried to pull him to safety, but with his head injury, he was ‘combative’. Lillian struck him in the temple, rendering him unconscious, then began dragging him from the flames.

Senior Minckler was standing in the hall during this process. Lillian Coburn then pushed Senior Minckler with one hand and drug Junior Minckler with the other. She managed to get them out of the burning building, but she suffered severe burns to her head, neck, and face in the process.

As the fire broke out and his mother’s heroics were being tested, Donald Coburn was asleep upstairs. Fortunately, he managed to escape.

The fire destroyed the hospital, and Mrs. Brashear was minimally insured. The doctors lost all their medical equipment, and the Scott property next door had partial losses. But no one was seriously injured except Lillian Coburn.

Lillian was sent to Reno, where she was a patient at St. George Hospital, and underwent numerous procedures and surgeries to mend her burns. She spent a full two years in recovery.

As word of her deeds spread, two doctors from Reno nominated Lillian Coburn for a Carnegie Hero Fund award. Testimony was given by numerous people, and Lillian was not only given the Carnegie Silver Medal, but a $1,000 award and $50 per month. She was also given the George McNeill Medal, which was awarded to only three people per year.

In Susanville, Lillian’s friends were thankful. Her closest friend, Viola Roseberry, had tried to tend to Lillian’s injuries before she had been removed to Reno for expert care at St. George’s.

As Lillian healed, she returned to work, settling in the San Francisco Bay area. In 1918, she was hired to work at the county infirmary in Oakland for $75 per month.

It would be nice to think that Lillian’s life turned out well. She had done so very much for others. She had struggled through immigrating to a new country, the loss of a husband, and severe injury in the fire, but continued her career caring for others.

But in 1920, as the Spanish Flu ravaged the country, Lillian’s 18-year-old son, Donald, who was in Navy training at Goat Island in the Bay Area, fell ill from the flu. Not long after, Lillian began to suffer its effects.

Donald died on February 6, 1920. Lillian knew that her life was waning. She hastily made her will, which included leaving $1,000 to her friend, Viola Roseberry, and on February 10th, just four days after Donald’s death, she died from the flu. Lillian and Donald are buried together in Colma, California.

With the destruction of the County Hospital, in the 1913 fire, the county moved to build a new modern facility. Property was purchased, just outside of town, on a hill overlooking the Valley.

In 1915, voters approved the money and work immediately began.

The contract was awarded to the James McLaughlin Co. of San Francisco for construction, and the Latourette Fical & Co., of Sacramento for the mechanical work. The architect was famed George Sellon. These two companies and Sellon were, at the time, working to build the new Lassen County courthouse.

By June of 1916, the hospital was completed, and the Memorial Club ladies worked to help get it set up and ready for the first patients. Almost immediately, it was deemed inadequate, but it served for many years as the most up-to-date facility in the area.