by Susan Couso

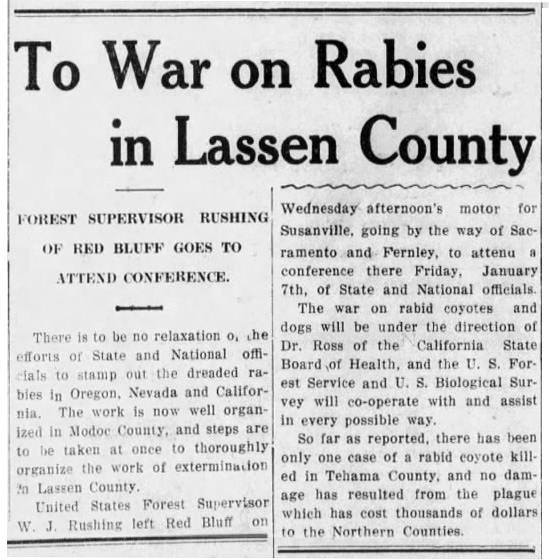

During the summer and fall of 1915, rabies had been discovered in Northern California. By November of 1915, the devastating rabies virus was beginning to make its way into Lassen County, and the county was put under a quarantine. As livestock began to die in large numbers, ranchers began to become concerned, and pet owners became anxious.

Rabies can infest any warm-blooded species, and that includes humans. It is not an easy death. The virus causes brain inflammation and is nearly 100% fatal if not treated within 10-days of infection. It is also 100% preventable if vaccine is given. Once the symptoms begin to show, it is too late.

The rules of the rabies quarantine required all dogs and cats to be muzzled and kept from roaming at large, and dogs or cats not in compliance were immediately killed.

A Quarantine Tax of $2 each was also placed on all dogs. This caused ‘Indignation Meetings’ to be held in Susanville, where people could voice their disproval. Just how do you keep a cat muzzled?

In response to this new edict, pet owners sent their dogs and cats out of the area for safe keeping. That caused a new threat of spreading the virus elsewhere, and officials appealed to people to keep their animals at home.

Nevada and Oregon enacted strict rules which forbid transportation of animals over state lines from the quarantined counties, and the settlements of Gerlach and Empire were concerned with infection of the deadly malady reaching their communities from Lassen County.

The county was divided into districts, and hunters were hired to keep their district under control. The Forest Service helped with this effort and were designated ‘District Inspectors’ who oversaw the hunters and their progress.

In Westwood, a woman filed a complaint against a Forest Ranger who had killed her “favorite dog”, simply because he had wandered into the street, and in Doyle, George Otis’ dog killed a coyote, and then had to be destroyed when symptoms began to show. Otis traveled to Berkely to receive the Pasteur treatment.

All wild animals were suspect, but coyotes got the worst of the deal. Bounties amounting to $2.50 were placed on them, and in six weeks, 1,326 coyotes were killed in Lassen and Modoc counties.

By the middle of January,1916 the tally was alarming. In Lassen County, 600 coyotes, 66 dogs, and 21 cats were killed. Livestock suffered, and there were 3 hogs, 146 cattle, 26 horses and 9 house cats who were found dead and suspected of falling to the virus, and coyotes were becoming scarce.

By the end of March, the coyote death count was up to 806. In the same period there were killed 109 dogs, 90 bobcats, and 93 weasels. For bait, 1,120 rabbits, 350 ground squirrels, and 310 magpies were used. A total of 1,217 traps were put out. Suspected rabies was reported in the case of 89 cattle, six hogs, six sheep, nine dogs, 22 coyotes and 10 horses. Through April, the pattern continued.

In May 1916, Frank Packwood fell ill. Not understanding that the rabies virus might have infected him, he rested. But soon, the symptoms became serious, and then it was too late. Authorities supposed that it was a puppy who had licked Packwood’s hand that had caused the disease and his death. In all, 16 men, women, and children from the Packwood household needed to travel to Berkeley to receive the rabies treatment.

In Adin, a rabid coyote came into John Holbrook’s barnyard and attacked his chickens. Holbrook’s dog attacked the coyote before Holbrook could get his gun and kill it. The dog was so badly injured that he had to be killed also.

As warm weather arrived, stock owners feared the worst. The livestock would be on the open range and completely unprotected. But the threat seemed to be waning. The end of May brought good news on the progress of efforts to eradiate the dreaded virus, and authorities declared that the danger had mostly passed. By October, rabies was considered ‘eradicated’, and in November, the quarantine was lifted, and rabies cases were declared “rare.”

Even so, new infections did show up, but authorities claimed that they were coming over the state lines from Nevada and Oregon. In Modoc County, two men were chased by a rabid coyote, one escaped by shimmying up a tree, and the other making it to safety in a cabin. The coyote was shot and killed.

The 1916 rabies epidemic in Lassen and Modoc counties resulted in the destruction of 2,707 coyotes and 178 wildcats. In addition, bounties were paid on 1,474 coyote scalps. Figures compiled by state board of health indicate that 362 head of cattle, 39 head of horses, 233 sheep, and 18 swine died from rabies or suspected rabies. Hundreds of head of stock found dead are also supposed to have died from rabies, but proof was not positive.

The scare was over, but the threat was still there. Today rabies is an easily preventable disease, and easily remedied if treated early. But rabies is as deadly as ever.